One suggestion is that they are buried beneath a mountain of good and not so good male Old Masters; the truth is, female old masters are quite scarce.

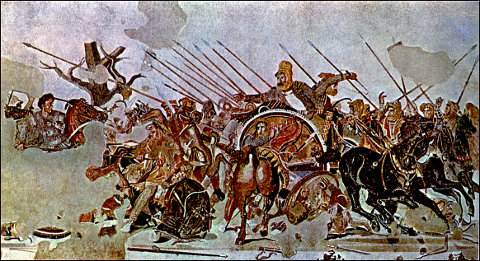

Helena of Egypt; Floor mosaic ‘Alexander the Great and Darius III in the battle of Issus’, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples.

Looking through the English-language 2006 edition of the French, Benezit’s dictionary of artists, (the print equivalent of the Encyclopædia Britannica for art enthusiasts) with its 14 volumes of 20,000 pages and 170,000 entries one sees that, before 1850, European women artists are a minuscule proportion of all the artists cited.

During Greek and Roman times Pliny the Elder and other Classical writers mention the existence of Greek women artists, most of them though, seemingly, working in the decorative arts. One of the few named female painters of the Greek era, Helena of Egypt, is believed to be the author of an important lost painting, Alexander the Great and Darius III in the battle of Issus.

A floor mosaic that would appear to be a later version of her painting was discovered in Pompeii during nineteenth century excavations at the House of the Faun and is now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples.

One of the most complete surviving forms of visual arts from the Middle Ages is the illuminated manuscript. A complex and expensive product it was a source of steady income for monasteries from the fall of the Roman empire onwards. Generally Gospel texts, they were richly decorated with rare and expensive pigments and burnished gold. These illustrated parchment books were the means by which the canons of classical art were transmitted through the centuries until the re-discovery of Roman and Greek statuary in excavations that were taking place in Rome during Michelangelo’s time.

The earliest post-Roman sources of this tradition were the Irish monasteries that created the Book of Kells a 7th century masterpiece of illuminated manuscripts, preserved in Dublin’s Trinity College. These beautiful creations were the product of anonymous monks but are also supposed to have been produced in convents of the period. The only identifiable woman artist of the Middle Ages that we known of is Hildegard of Bingen 1098-1179 a Rhineland Prioress.

Fine-arts painting, that today we see from our contemporary perspective as a prestigious and important cultural activity from which women were, for different reasons, unjustly excluded was not until recently considered a particularly respectable trade. It is unlikely that women would have wanted to be associated with such a socially unacceptable activity. Women of birth and rank up until the nineteenth century were taught drawing and watercolour painting as part of their general education an activity abandoned when they married or, at most, practiced for capturing scenic views when travelling abroad. Women were not under pressure to work for a living and their family commitments greatly circumscribed their abilities to compete in the commercial market. Important artists such as the independently wealthy Impressionist Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) and the rentier, Berthe Morisot limited their subject matter to children and maternal subjects by working in the confined space of the home or the nursery.

Germaine Greer, Anglo-Australia’s answer to Erica Jong, published, in 1979, an important and carefully thought out book on women Old Master painters and their work, ‘The obstacle race.’ It broke the log jam of history of art books until then dominated by exclusively male Old Masters. The book’s numerous illustrations confirmed, however, that the majority of Renaissance women were not outstanding painters with, obviously, some exceptions that included Artemisia Gentileschi or, later, Angelica Kauffman and quite a number of Rococo painters.

There is nothing remarkable in this. The majority were the daughters of artists and learned to paint in their fathers’ workshops. Equally, the sons and grandsons of prominent artists working for their fathers very rarely rose to prominence. They rode on the tailcoats of the successful works for which their fathers had gained notoriety and usually, using the patrimony of the Master, studio drawings, cartoons (full-size pencil drawings) and bozzetti turned out copies, reworkings or variations of the masters successful works, often maintaining the workshop’s output for several generations and with increasingly inferior quality. Gifted male artists, on the other hand, came largely from outside the art trade and having served an apprenticeship with a good or prominent working painter owed their eventual success to innate talent.

Jacopo Tintoretto’s daughter Marietta Robusti, was a good example of a girl growing up and assisting her father in a studio environment. Early writers, speaking about Tintoretto refer to his morbid affection for his daughter and her habit of accompanying her father on his paintings projects dressed as a boy. Marietta, like her German mother, Tintoretto’s mistress before his marriage to Faustina de Vescovi the daughter of an establishment figure, was a portrait-painter of talent.

Author in front of Tintoretto’s house in Venice.

She was sufficiently important to be offered the post of court painter, at the court of Philip II of Spain but preferred to remain in Venice. Marietta Robusti married Mario Augusta a jeweller but died aged thirty in 1590. None of her works or those of her mother have, to date, been positively identified except, possibly, a self portrait in the Uffizi.

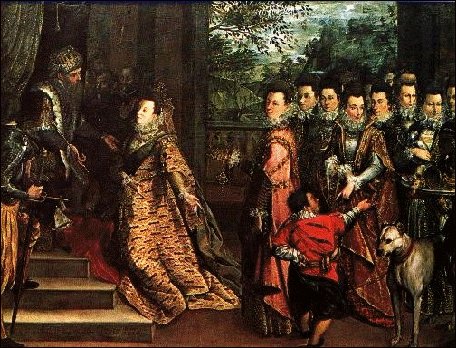

Lavinia Fontana, (Bologna 1552 – Rome 1614) ‘Visit of the Queen of

Lavinia Fontana, (Bologna 1552 – Rome 1614) ‘Visit of the Queen of

Sheba to Solomon,’ (after1589), National Gallery of Ireland.

Another artist who got her start in life working in her father, Prospero’s workshop was Lavinia Fontana. She developed a Mannerist technique with some overtones of Venetian style and colour. She married one of her fathers assistant Gian’ Paolo Zappi a member of the Bologna nobility whose descendant, Count Zappi of Imola, has today in his possession an early self portrait. She had an extensive and successful workshop and broke out of the mould of portrait painting traditionally reserved for women to undertake important history and religious paintings. She was unafraid of large-scale projects, for example, the, ‘Visit of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon, that the author restored. Lavinia’s painting was hidden away and lost to view for many decades in the cellars of the National Gallery of Ireland. In the process of removing generations of blackened varnish the painting’s beauty and unique style was uncovered allowing us to identify the artist. It is accepted by historians that the painting is a group portrait of members of the Mantua, Gonzaga family.

Gian’ Paolo Zappi himself acted as her agent and as her painting assistant, negotiating paintings contracts and completing background features of her works such as drapery and costumes. This may account for the noticeable stiffness the persons depicted in this composition possess. One of her portraits paintings is also in a private collection in the Principality of Monaco.

Andrea Pozzo, 1642–1709, Allegorical illustration of a Female portrait painter.

A similar situation prevailed in Dutch Golden Age painting. The prominent woman painters Judith Leyster (1609-1660) seems to have appeared unexpectedly on the Utrecht scene as a fully fledged artist and is remembered largely for being a member of the Saint Luke Artists Guild and as the wife of Jan Miense Molenaer another successful artist. Her works were often confused with those of Frans Hals until the 19th. century when she was rediscovered and her paintings correctly identified. Following her marriage, the quality, format and quantity of her paintings declined, it would appear, because of domestic commitments.

After the High Renaissance the true emancipation of women painters occurred as the result of portrait painting, in which they successfully created a personal niche. Prominent Rococo artists like Rosalba Carriera, Elizabeth Vigée-Lebrun, and, later, the marvellous anti-establishment Rosa Bonheur, became important painters catering to the aristocratic and bourgeois market. Women remained prominent in this specialised field through to the twentieth century. Portrait painting, especially of women and children permitted many of them including Gwen John, Augustus John’s sister, to maintain independent economic and artistic careers.

If you need an appraisal of your old painting, contact Matthew Moss at Free Paintings Evaluation.